While Amazon has approached Sidewalk, an endeavor in connecting smart devices to a neighborhood mesh Wi-Fi, in a "sophisticated way" with privacy in mind, experts are still wary of how effective this project will be from a security standpoint.

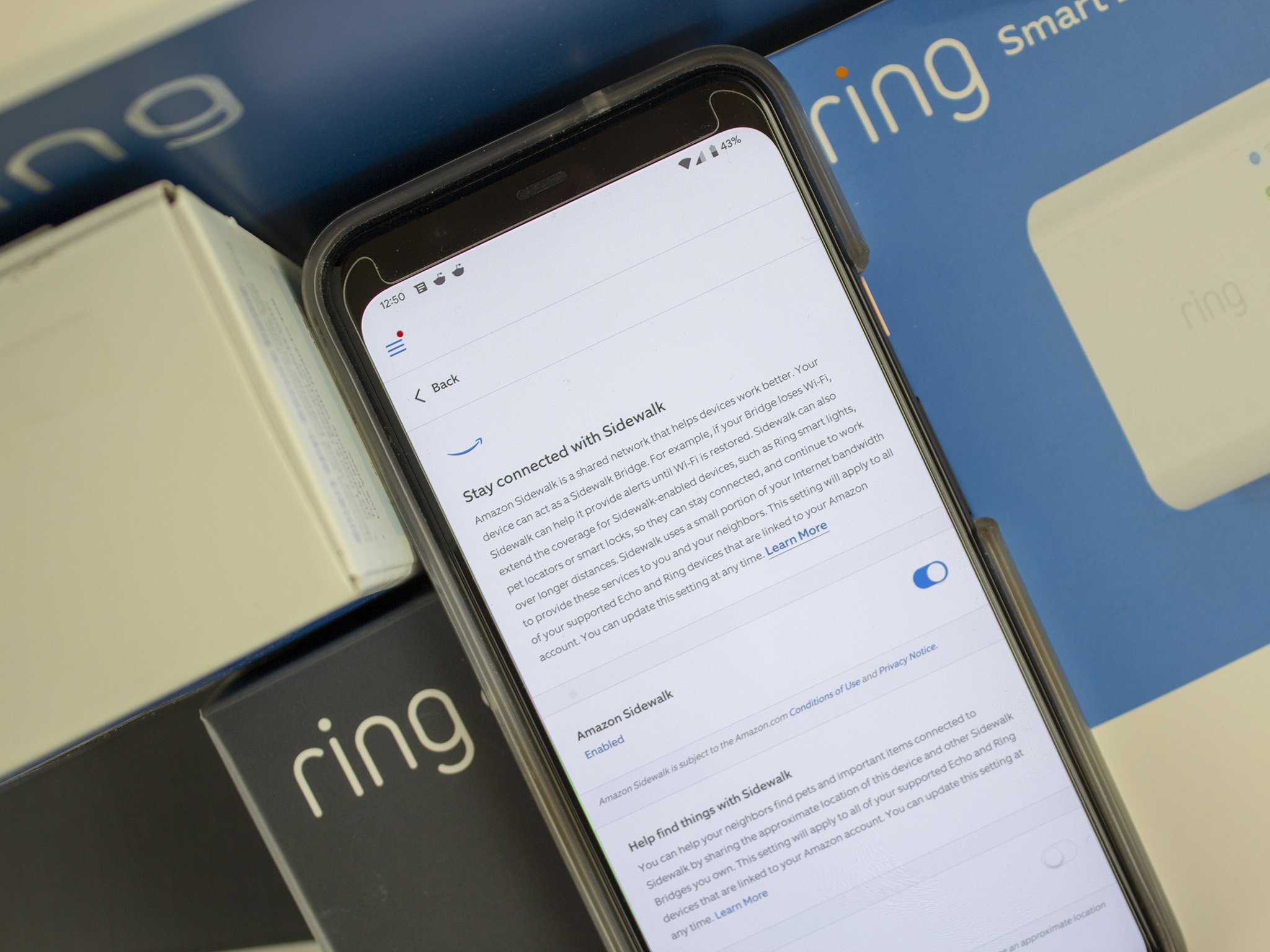

Amazon announced last week that customers have until June 8 to opt-out of its latest project to keep smart devices connected at all times by using a mesh Wi-Fi system. If you don't want to participate here's how to opt-out on Echo devices and Ring devices.

The program, which was initially announced in September 2019, uses a low-bandwidth shared network that will use part of your home Wi-Fi to connect to Amazon Echo devices, Ring security camera and lights, and Tile Bluetooth trackers. The mesh Wi-Fi is helpful when your device loses connection, at which point it will automatically connect to the neighborhood Wi-Fi over the 900Mhz channel.

According to the company's privacy and security whitepaper, the project was "carefully designed" with privacy protections in mind, specifically on how it collects, stores, and uses metadata.

For example, each user device at registration to the program will have a "unique session key" with the Sidewalk Network Server (SNS) and Application server. Once the device has been identified and is part of the system, the SNS won't be able to identify a user, and makes it "difficult for anyone, including Amazon, to piece together activity history over time."

Information is wrapped in layers of protection, but nothing is 'zero-risk'

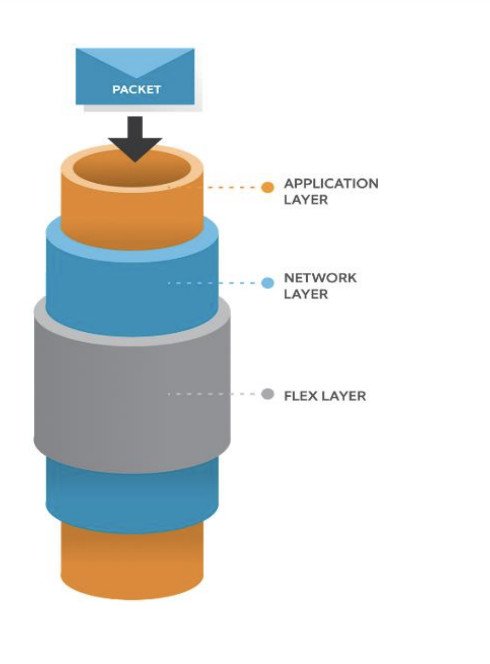

Amazon also notes that information for devices to work on the network will travel in, what it calls, a "packet" that will have three layers of encryption protection. The encryption is done to "ensure data is visible only to the intended party."

"This approach to encryption means that Amazon will not be able to interpret the content of commands or messages sent through Sidewalk by third party services or endpoints (applications," Amazon writes.

John Verdi, vice-president of the Future of Privacy Forum, an industry-backed nonprofit based in Washington, D.C., said in an interview what makes this program strong from a privacy front is that only Amazon devices can participate as well as trusted partners. He added that users can't just add a trusted device to the program like an iPhone or a user's personal laptop.

"What that means is that Amazon can limit the physical hardware devices that connect to Amazon manufacturer devices and trusted partners. Not just any device can connect. There's the validation of the device itself," he said.

Verdi also added that the program wouldn't use a lot of data that is typically used for streaming video. Sidewalk would only use up to 500MB of bandwidth a month, a relatively small amount — though not insignificant for people on a fixed-bandwidth connection.

"The Sidewalk mesh network [likely] doesn't use bandwidth that will materially impact the owner's online experience," he said.

Verdi added that there is no "obvious or straightforward way" in which a third party could manipulate the system.

"Now, nothing is zero-risk. There's always a chance that a novel exploit or a novel method performed by a malicious actor could come to light. We don't know. But when you look at the safeguards that are in place, they are serious technical safeguards. They are not trivial," he said.

"There's a risk with any product, but having said that, does the risk look well mitigated? Yes."

Whitepaper is full of complicated jargon

Sumit Bhatia, director of communications and knowledge mobilization with the Cybersecure Catalyst at Toronto's Ryerson University, said in an interview that Amazon's whitepaper details security and privacy in a detailed manner, but uses sophisticated language that makes it difficult for a regular person to understand how the system works.

Bhatia said that while this is a step towards building a smart neighborhood or city, there needs to be a proper framework with systems that have been tested before implementing a large-scale project like Amazon is trying to do.

"The fact that they (Amazon) are not launching this in a closed group but launching it in an entire country of people, speaks to the approach that they want to take," he said. "They are using this mass approach across the U.S. as, in my opinion, an opportunity to gather data, and a lot of people who are (part of the opt-in) are guinea pigs for that data, but at the cost of there being potential threats and ramifications that we don't know."

And while Amazon has laid out clear privacy guidelines, Bhatia suggests that this is another way for Amazon to create a user profile this time by creating a connected-service program.

"Amazon is being very strategic about how they're doing this because they're doing this without being somewhat of an internet service provider, but still being able to claim ownership of a network where they can aggregate data of a larger pool of people," he said. "That to me is problematic."

Without beta testing the program, how does Amazon know it's effective?

Rebecca Herold, CEO of the Privacy Professor Consultancy and a privacy expert, agreed with Bhatia in an interview, adding that the white paper includes "copious amounts of text and jargon."

She notes that despite Amazon explicitly detailing its encryption method, which is "very protective," there are still issues.

"We've already seen how you can actually use the mesh network to basically decrypt rather easily using simple tools like configuring IP tables that will tell devices to forward traffic from all Echo devices or all other types of IoT devices to a certain proxy. And by sending it to a certain proxy it can replace the Amazon Server Certificates.

"The way it works is basically those IoT devices are going to accept the certificate of whoever answers them first. I just want to sit around in my network in my neighborhood here and figure out a way to incorporate my devices into the network and I could probably fool a lot of those devices into trusting me," she said.

Herold applauded that Amazon is also trying to help you find your pet, lost keys, or in some cases patients suffering from dementia or Alzheimer's in a more efficient way. But it also concerning if you have a stalker, she said.

Like Bhatia, Herold said she was worried there wasn't a proven beta for the program.

"How did they beta test this thing? How did they even make sure that the testing was thorough and that it'll work? When you're dealing with new Wi-Fi protocols, which basically they created, you need to test them very thoroughly. It does not seem so, especially in some of the online groups that I've been tracking where people have opted out," she said.

The program is a win for consumers: Higginbotham

Despite, Bhatia's and Herold's reservations, Stacey Higginbotham, a technology journalist who focuses on IoT devices, explains in her latest newsletter that overall Amazon's program is a win for consumers.

"I firmly believe that this network will be an overall benefit for consumers and developers, who can add new features or build new, cheaper devices that take advantage of it," she wrote. "The privacy and security features are legit. Again: Amazon doesn't see your data and it doesn't see the developers' data. Neither does anyone else. In other words, I think you should opt-in."

She does add that if you're a "control freak," or someone who is well-versed in the security protocols but is still wary, they might opt out.

"Most came to the conclusion that they simply don't want their home network to be used as a bridge for unknown packets. What if those packets were illegal? What if the ISP didn't permit that type of use? I can't argue with control freaks, but I can point out that Apple's AirTag and FindMy network run on a similar principle of using your home or cellular data to share Bluetooth location data across an ad-hoc mesh network," she wrote.

0 Response to "You Can See More: Amazon Sidewalk is revolutionary, but its scope worries privacy experts"

Post a Comment